The cargo-quickinstall journey - how I made a thing for installing rust programs quickly

I made a thing.

I made a thing that I threw together in a week.

I made a thing that is horrifically complicated, and held together with hot glue and string.

I made a thing that people seem to be using.

Halp!

Pre-built binaries of Rust programs

Back when I was working at Red Badger, we had some GitHub Actions pipelines that relied on some tools that were written in Rust. We had our GitHub actions cache set up correctly and everything, but every so often we would blast away the cache, by some innocent-looking operation, like bumping a dependency. This would result in a dog-slow build, as it rebuilt all of the tools that we were using, before even starting to compiling our own project.

When that project wound down, I had some bench time between projects, so I decided try doing something about it. I decided to build a service that would pre-build your Rust tools for you. That way, whenever you would usually write something like:

cargo install ripgrep

you could write:

cargo quickinstall ripgrep

This would install pre-compiled versions of any binaries in the crate. If we did’t have a pre-compiled version, it would fallback to cargo install automatically.

The initial implementation of cargo-quickinstall was hacked together in less than a week. I also took the opportunity to make as many terrible architectural decisions as possible. Proper resume-driven development. Good times.

Do the thing

At Red Badger, there is a saying “Do the right thing. Do the thing right”.

“Do the right thing” is about finding ways to make sure you are actually making something that people find useful. “Do the thing right” is about getting products into the hands of users in a sustainable way, so that we can gather feedback and and iterate quickly.

I decided to start by building the feedback bit first. If my system knows which packages most people want, it can “do the right thing” without my intervention, by making sure that those packages get built. Having download counts for my packages would also let me know valuable my thing is, and whether I should keep doing it.

Stats Server

I knew that the requirements for the stats server were pretty simple, and also that the rest of the system would function just fine without this piece of the puzzle. I optimised for ticking things off of my tech bucket list, rather than building a rock-solid server.

I started out by creating a Cloudflare Workers project in Rust, using their Wrangler devtool, and their KV store. Rust support for cloudflare workers had only just come out at the time, and I quickly realised that taking this approach would be an uphill battle. There weren’t even official rust bindings to their KV store at the time. I had also read somewhere that their KV store was heavily read-optimised (as-in “please think of this as a configuration store, and don’t try to make more than 1 write per second”, or something). I had grand dreams that I might one-day receive more than 1 request per second, so I decided to switch tack.

The boring choice would be to spin up a Heroku app and write to PostgreSQL. That was too boring though. What other fun resume-expanding technology stack could I use?

One of the most fundamental requirements for cargo-quickinstall has always been that it shouldn’t cost me anything to maintain, so stringing together free-tier teaser offerings was the order of the day.

I remembered meeting with an ad-tech company at a careers fair a few years earlier, and they had a fun architecture. They didn’t have any of their own servers in the hot loop of serving customers. They would serve everything from CDN, including tracking pixels, and then have a cronjob that parsed the CDN logs and used that to generate invoices to their customers. Clever, right? Entirely too web-scale for my own good.

Following this piece of slightly inappropriate architectural inspiration, I span up an empty Vercel project, and started spamming it with requests to random non-existent pages. I then hooked up the log drain to sematext. My client would make a request to a non-existent page, and immediately receive a 404 response. I would then periodically query the sematext Elasticsearch API. No cold-start lambda delays to worry about 1. Brilliant.

Artifact Storage

For artifact storage, I picked a service that I had used before for hosting debian packages, specificallyJFrog’s Bintray service.

I hacked up a script to build a package and upload it to Bintray from my laptop. I ran it on a single package to get me started, and moved on.

Client

Next on the list was the cargo-quickinstall client.

This is basically a glorified bash script.

I wanted cargo install cargo-quickinstall to be as quick as possible, so I only used things that were in std, and shelled out to the system’s curl and tar binaries to do the actual work. curl and tar are both available on modern Windows boxes by default, so this turns out to be a surprisingly portable choice. I also initially did json parsing with jq, but this has since been replaced with tinyjson because apparently nobody has jq installed (they don’t know what they’re missing).

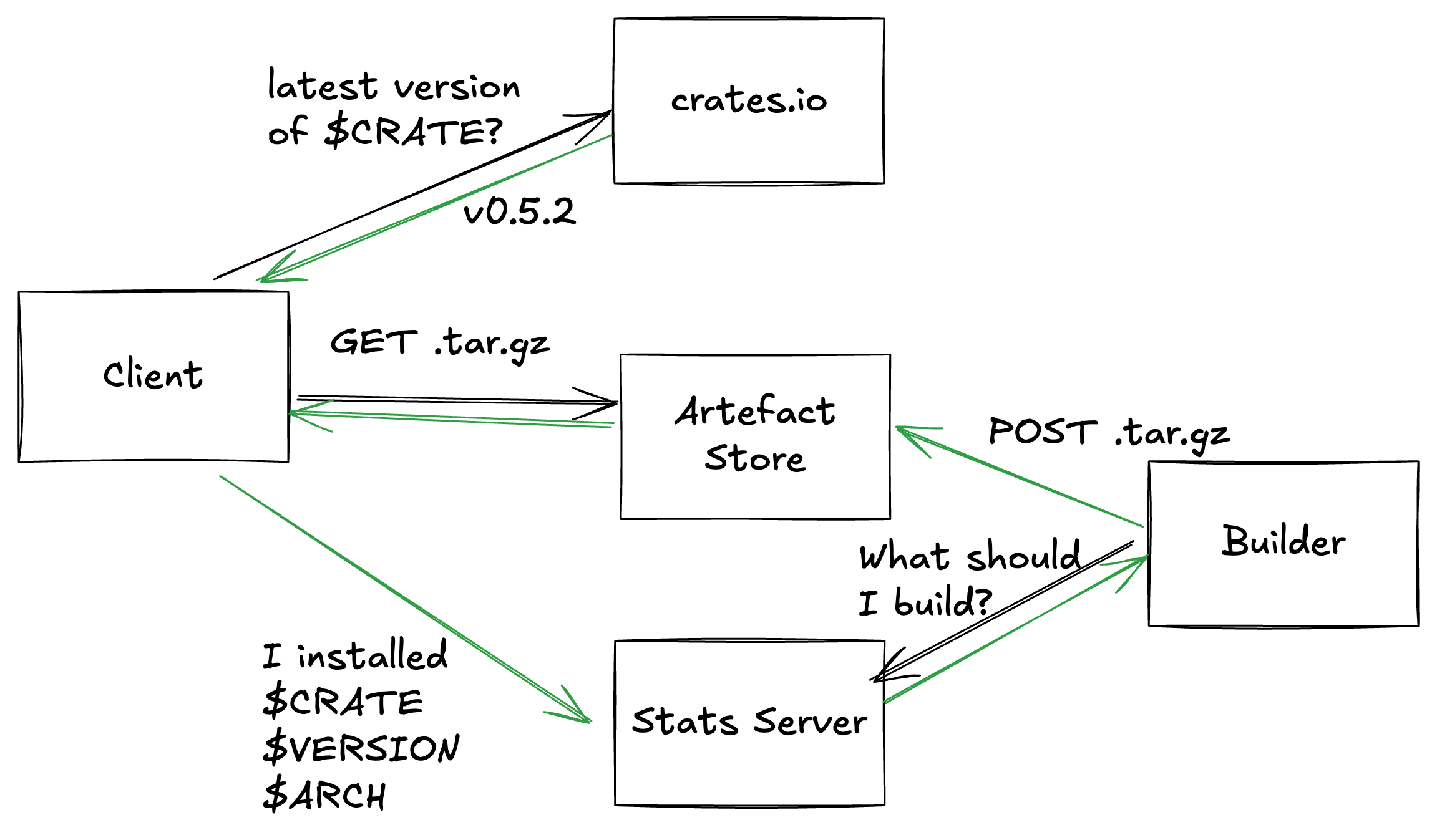

The initial client basically did this:

Automated Builder

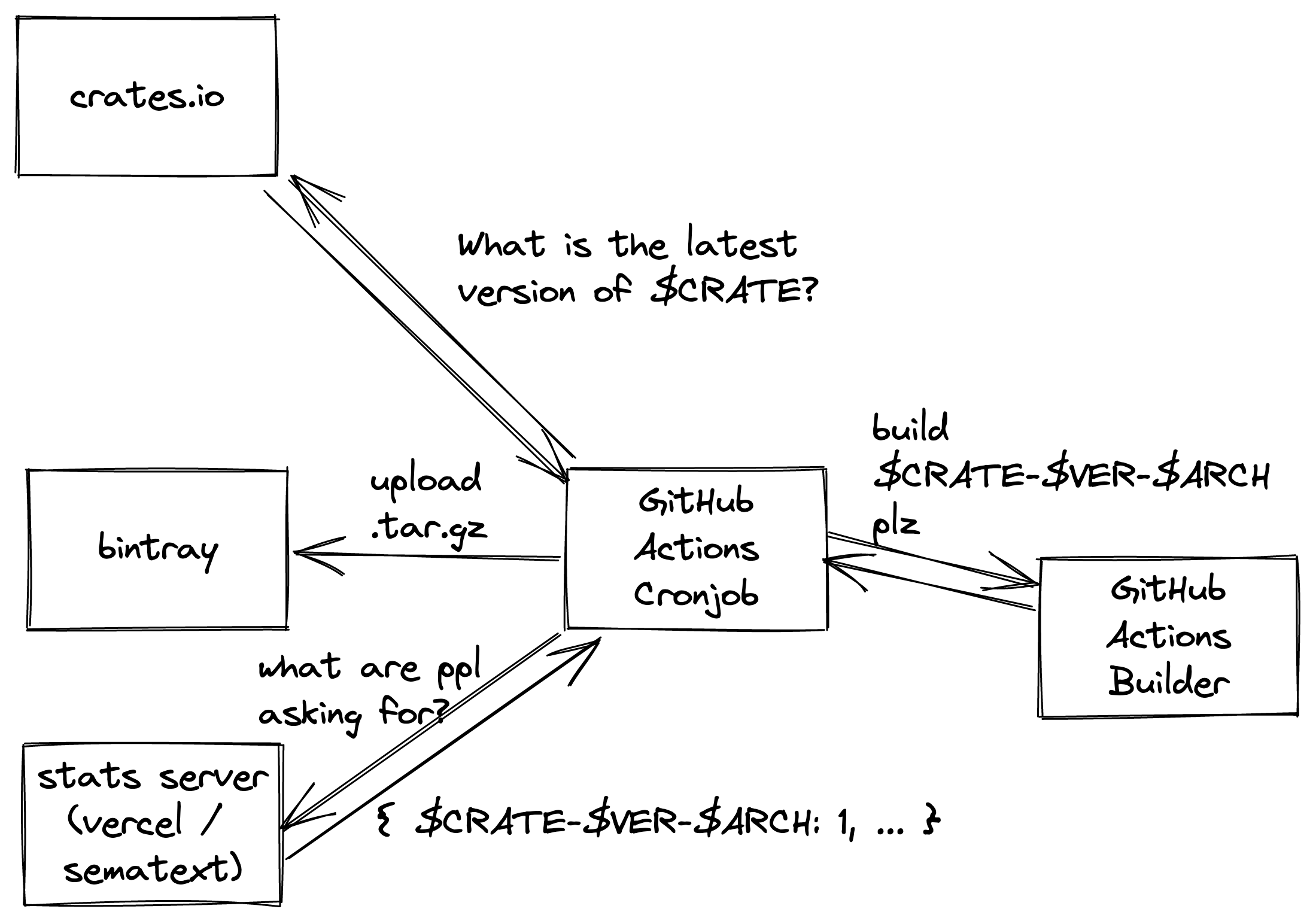

The automated builder is responsible for this half of the architecture diagram:

The initial implementation got its list of requested crates from sematext’s Elasticsearch API. It was pretty simple - it would just make a list of all requested packages, and try to build + upload the first one that we didn’t already have a package of in Bintray. If there was nothing to do then it would just build cargo-quickinstall for good luck (which only takes a couple of seconds, so isn’t that much wasted work).

Security and Trust

It’s worth digging into the cargo-quickinstall trust model at this point.

The trust model is currently:

- You trust the author of the crate that you asked for, and its dependencies.

- You trust me to be acting in good faith, and to have configured GitHub actions and GitHub releases correctly, and my sandboxing to be adequate.

- You trust GitHub not to replace everyone’s released binaries with cryptomalware.

This means that (assuming that you trust cargo-quickinstall, and that our sandboxing is solid) by running cargo quickinstall $CRATE, you’re not forced to trust anyone that you’re not already trusting by running cargo install $CRATE.

cargo-quickinstall does not trust the author of any package on crates.io. As soon as we have run the crate’s build.rs or any proc macros, we must treat the build box as compromised. There is some gymnastics involved in achieving this, so bear with me.

GitHub Actions Gymnastics

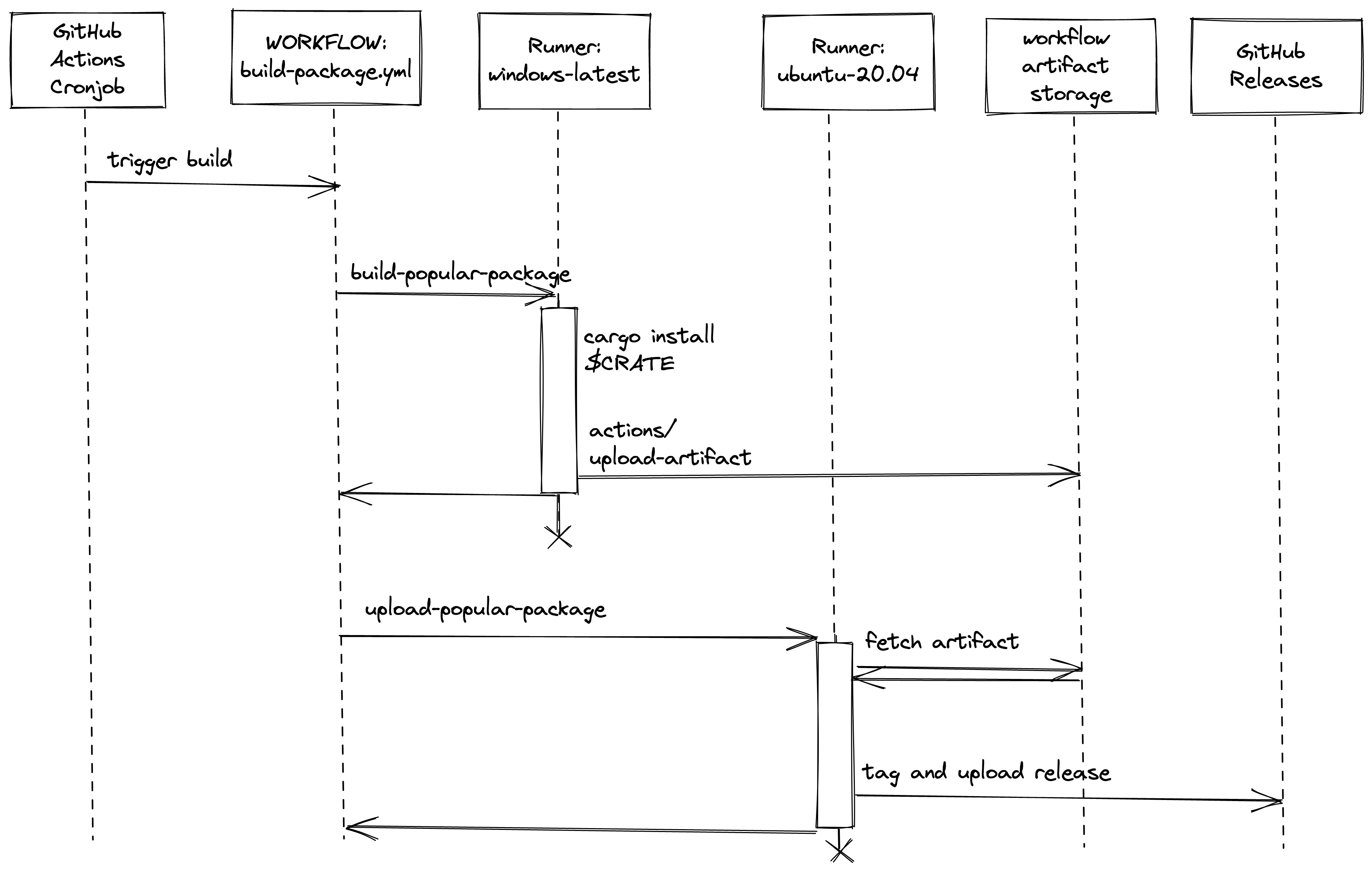

The cronjob works out which crate needs to be built next for each target architecture, and which runner OS we need to build it on.

The workflow that does the building is given $CRATE $VERSION $BUILD_OS and $TARGET_ARCH. We currently supply these variables by running sed over a template, and committing the result to git. If I was writing it again today from scratch, I might revisit this decision, but this works well enough for now.

We spin up a runner with $BUILD_OS and permissions: {} on it, and do the build. This essentially runs cargo install $crate and then tars up the resulting binaries and uses actions/upload-artifact to upload it with a known filename, so that it is available for other jobs in the same build pipeline.

Security notice: I’m assuming that all runners are able to use actions/upload-artifact without any extra creds. ~I’ve not really dug into it that much.~ If it turns out that the runner is being given some kind of god token, and that token is available to $CRATE’s untrusted build.rs for doing anything other than uploading build artifacts then we’re in big trouble. If you believe this to be the case, please email me so that I can stop building new packages and do a proper audit/redesign.

Once the builder is finished, we throw it in the bin, and spin up a new ubuntu-20.04 runner. This downloads the tarball from actions/upload-artifact2 and uploads it to GitHub Releases (previously bintray).

By doing this whole dance, we ensure that a malicious crate author can only poison the tarball of their own crate, or any crates that depends on their crate. If you run cargo install $CRATE then you already trust every crate in $CRATE’s dependency tree, and you already trust GitHub for the crates.io index. Assuming that you trust cargo-quickinstall and that our sandboxing is solid, by using cargo install $CRATE, you’re not forced to trust anyone that you’re not already trusting by running cargo install $CRATE.

There are probably massive holes in this logic. Even if it’s all sound, cargo-quickinstall has never been audited. If you work at Microsoft/GitHub and/or would like to sponsor a security researcher to help me audit this, please leave a comment on this issue or contact me privately.

EDIT 2022-07-24: When pair-reviewing this post with @alecmocatta, he pointed me to a github security article on the matter. It seems sensible to assume that the runner for the “build” is a VM that contains both the untrusted code and an orchestration process that has access to the GITHUB_TOKEN for the whole build.

He also advised me not to trust any isolation boundary that’s less strong than full-on VM isolation.

This stalled me for a while. I came up with an excessively complicated scheme, and we agreed that it would probably work, but was very unsatisfying. When I sat down to implement it on the weekend, I stumbled on a mechanism to neuter the GITHUB_TOKEN that is sent to the runner. The fix ended up being a single line.

I have not yet found a way for a malicious crate to extract the secret and use it to do anything. I also don’t have any reason to believe that anyone else has done so. I will therefore be keeping all previously built packages published in the repo as-is. If you believe that this is unwise, and would like to help me implement a better security process, please comment on this issue and I will set up a call to pair on it.

Bootstrapping the package list

There is a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem with the approach I have described so far. If you don’t have any users then you won’t have any idea which packages need to be built. New users will always find that we don’t have the packages that they want, so they will stop using our service. This means they will not tell us the names of any more packages that they want building.

To break this cycle, I made a list of popular packages by grabbing the html from https://lib.rs/command-line-utilities and pulling out the package names into a flat text file using pup and jq.

Skipping broken packages

Not all crates build on all platforms. Initially, my builder didn’t have any memory of what it had attempted to build, so when it came across a package that it couldn’t build, it would get stuck and attempt to rebuild it every hour until I manually excluded it. It also did each of the platforms in series, so a broken windows build would block progress on all platforms. It was also racey, so if a build took over an hour (or if I got impatient and triggered multiple builds in an hour) it would sometimes build the same package twice, and then crash when trying to upload it.

This is where the “sed the template and commit it to git” approach comes in. There is a branch for each target (trigger/$TARGET), and each time the cronjob builds, it checks out each trigger/$TARGET branch, using git worktree, and checks what it last attempted to build. It then walks down the list of popular/requested crates, and makes a new commit to trigger a build of the next crate after the one that was last attempted. We still do a lot of useless builds of packages that would never compile, but at least we weren’t head-of-line blocking anymore.

Later, when we started pushing tags for each successful build (as part of the switch to GitHub releases), we were able to detect repeatedly-failing builds and automatically add the offending packages to the exclude list. This process is a little fragile, and it currently errs on the side of building known-broken packages occasionally, but it’s better than nothing.

Free Tiers Don’t Last Forever

The danger of relying on free-tier stuff is that your provider is not beholden to you in any way. They may take away your service at any time.

The first service to fall was Bintray. Bintray was still serving my compiled crates read-only, and I had a bit of time before they would start deleting them entirely, so I wasn’t in too much of a rush, but if I didn’t find an alternative host eventually then I would have to put cargo-quickinstall in the bin.

Around this time, I was mentoring a Hack and Learn, and the spotify-tui maintainer pointed out that they use GitHub actions to make their releases, and that the release artifacts would show up with predictable URLs. I kicked off a new verson of the builder that could upload to GitHub Releases, and then made a release of the client which could fetch from both places.

The next free-tier service to go away was sematext. When sematext ended the free tier that my log pipeline was using, I decided that it was probably time to pick a more traditional architecture. I added a couple of typescript endpoints to my Vercel site so I was no longer relying on logs of 404 errors. Boring. I like boring. Boring is good, especially for things that people are using, and that I need to actually maintain.

The joy of working with other people 🤝

I have really enjoyed working with external contributors on cargo-quickinstall. The client is super simple, so it is reasonably approachable for beginners. After mentoring two Rust London Hack and Learn events, most of the low-hanging fruit has been picked, but there are approachable issues that show up from time to time. If you want to have a go at one, check out the good first issue.

Next Steps

There are a few open issues on the board, and I’m happy to mentor people on any of them. The issue that I’m especially interested in mentoring someone on is the one for building static binaries for non-ubuntu-20.04 support, and shelling out to cargo-binstall for the more complex fallback behaviour.

At the moment, there are no time-critical issues on the board (no security issues, and nothing that represents a regression for existing users in CI), so I am mostly leaving things open and offering mentoring on them. It is more valuable at the moment to get more people familiar with the codebase, and improve the bus-factor of the project.

Speeding up cargo build as well

The other reason for me taking this approach with cargo-quickinstall is cargo-quickbuild. This is a project idea to take parts of dependency trees, rather than just the end-result. I have started progress on this over in a new cargo-quick repo. The idea is to have a tool to make from-scratch builds quicker, by providing a central repo of prebuilt crates (think docker layers for your target dir). It will have the same trust model as cargo-quickinstall, but a slightly more complex architecture. Once quickbuild has come along a bit further, I will port the quickinstall builder to use it, and then merge cargo quickinstall into the cargo-quick repo.

This raises the question:

Why not use

sccache,nix,bazelorcargo-chef?

To avoid bloating the end of this post, I have split this out into its own post. The conclusion of which is:

Rust’s tooling excellence owes a lot to the unifying influence of

cargofor build + docs + testing. Its major shortcoming is long build times. My aim with quickbuild is to meet users where they are, becausecargois an excellent place to be. I’m hoping to produce meaningful speed-ups of from-scratch builds, without requiring configuration changes for the user’s computer/project.I also aim to build on shared infrastructure, available to all, so you don’t need any involvement from finance or your ops team. I will be making use of free “open source tier” compute resources for building my packages, but they will be available for use by anyone to reduce their build times and CI costs, as long as they are happy to share their rust flags, and the list of dependencies from their Cargo.toml.

I am coming to the end of my time at Tably and I plan to spend August house hunting and working on quickbuild, before looking for my next job. If you would like to become the first sponsor this work, please go to my GitHub Sponsors page.